Are you going a little ‘Brumas’? The Opie Archive opens a window onto a 1950s phenomenon

The cataloguing of the Opie Archive of school-children’s play, lore and language is yielding some fascinating examples of playground terminology. Some is familiar from our own childhoods but one contribution from Sale County Grammar School for Boys dating from the early 1950s had us puzzled. The contributor had submitted the word ‘Brumas’, translating it as ‘a little bear on top – a bald man’. Our confusion was compounded by further information from the child’s teacher and Opie correspondent who indicated the presence of some punning word-play, ‘A bald man – Brumas (the “Bare”)’. It took some 21st-century web-surfing to shed light on this bald spot in our knowledge.

So who, or what, was Brumas? Our search for the answer opened a window onto a phenomenon of the early 1950s – the first ever polar bear cub born at London Zoo in 1949. Although a female bear cub, the press had reported that the bear was male. Given her portmanteau moniker through the combining of her keepers’ names (Bruce and Sam), Brumas was a sensation. Her presence at London Zoo boosted visitor numbers as members of the public flocked to catch a glimpse of the new arrival. A report from The Observer newspaper in April 1950 records people standing ‘in solid blocks’ around the polar bear enclosure from 9am to 7pm to catch a glimpse of ‘the baby’, as this clip shows:

Not only a celebrity bear, Brumas was also a brand, with books, toys (such as this mohair model of Brumas and her mother Ivy held at the V&A Museum of Childhood), and even soap manufactured in her image. Her popularity also made her the subject of song, as this cabaret performance demonstrates. Not surprisingly, Brumas became a national phenomenon. Sir Michael Palin remarks in his 1992 account of his travels from ‘Pole to Pole’ that he is keen to see a polar bear, having been ‘brought up on Brumas’.

Equipped with this knowledge we’re now able to interpret this multi-layered archive entry. The joke rests in the use of the homophones ‘bear’ and ‘bare’ and relies on the widespread awareness of bear-of-the-moment Brumas, who came to public attention via popular media and commercial influences. Perhaps too, the widespread assumption in the media that Brumas was male affirmed the connection with male pattern baldness.

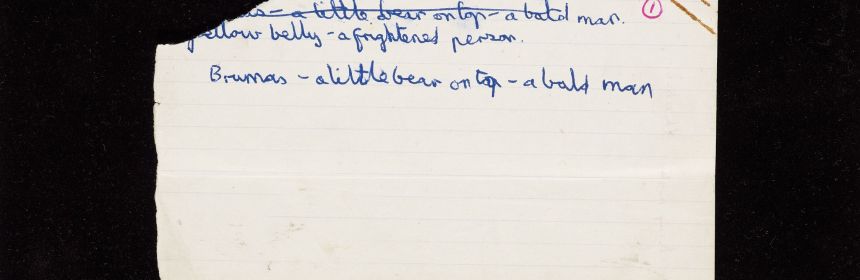

Reference to Brumas in teacher’s letter to the Opies (cropped). Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Opie 1 fol. 146v

We will never know who the unfortunate ‘Brumas’ of Sale was and are as yet unclear whether the epithet was common or confined to this area. However, this data demonstrates how assemblages can act as a prompt for our own cultural responses, informed here by the ‘desire for fun’ that the Opies observed as embedded in schoolchildren’s language, with nicknames an exemplar (The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren, 1959, p. 154). In this case, Brumas’ fame became a stimulus for playful use of language that now, at this historical distance, recalls an event that impacted on the national consciousness. Brumas died in 1958, but her linguistic legacy lives on in the Opie Archive.

Header image: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Opie 1 fol.143r